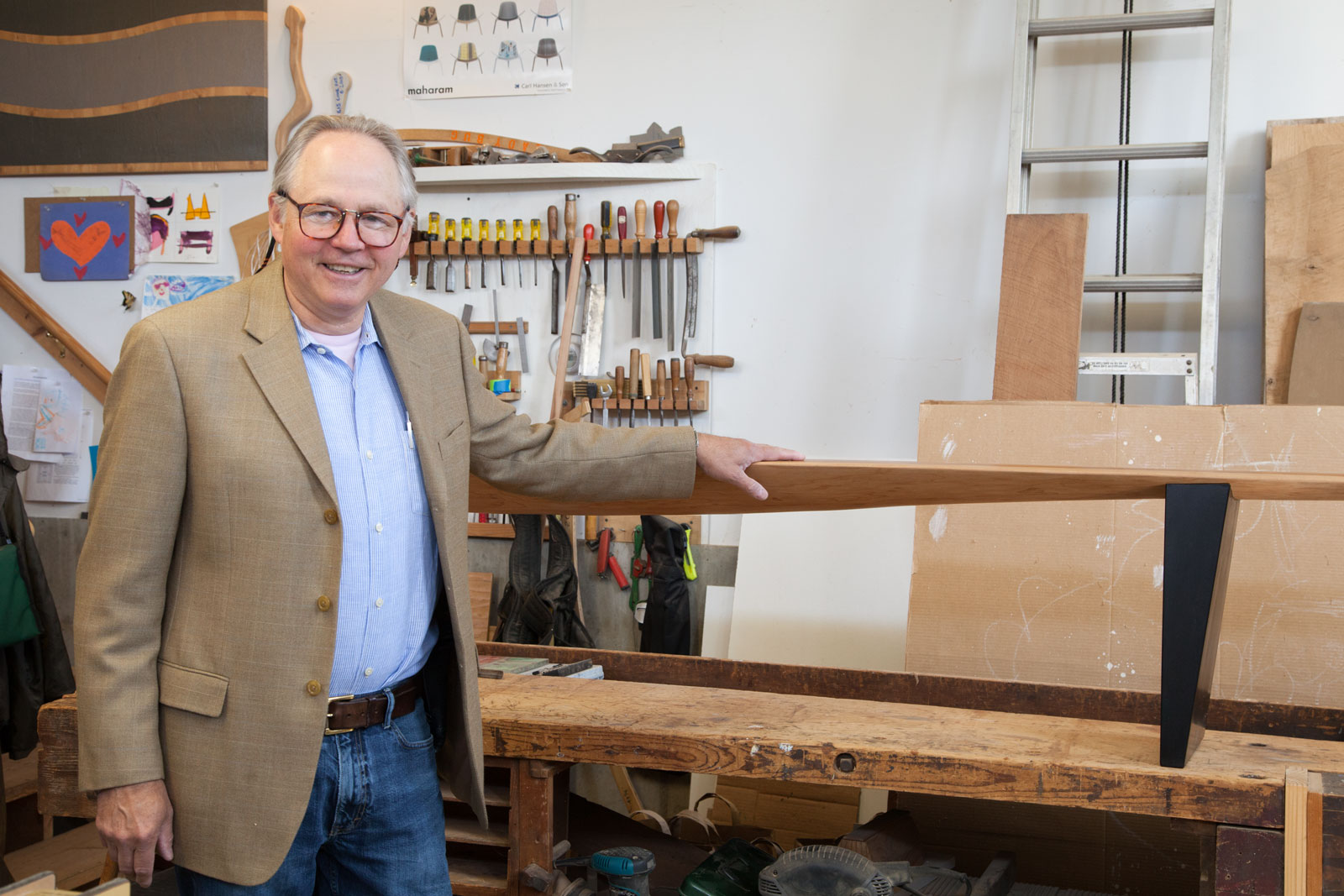

John Scofield is and artist and designer living in Sharon, CT with his wife Bartley Johnstone, and their daughter, Evie. His work has been published and reviewed in Arts, Design Times, Elle Decor, Interior Design, Landscape Architecture, Metropolis, New York Times, Progressive Architecture, Traditional Home, Vogue, and other publications. We visited with John and Bartley a couple of weeks ago, and we present to you; “At Home with John Scofield.”

At home with artist John E. Scofield

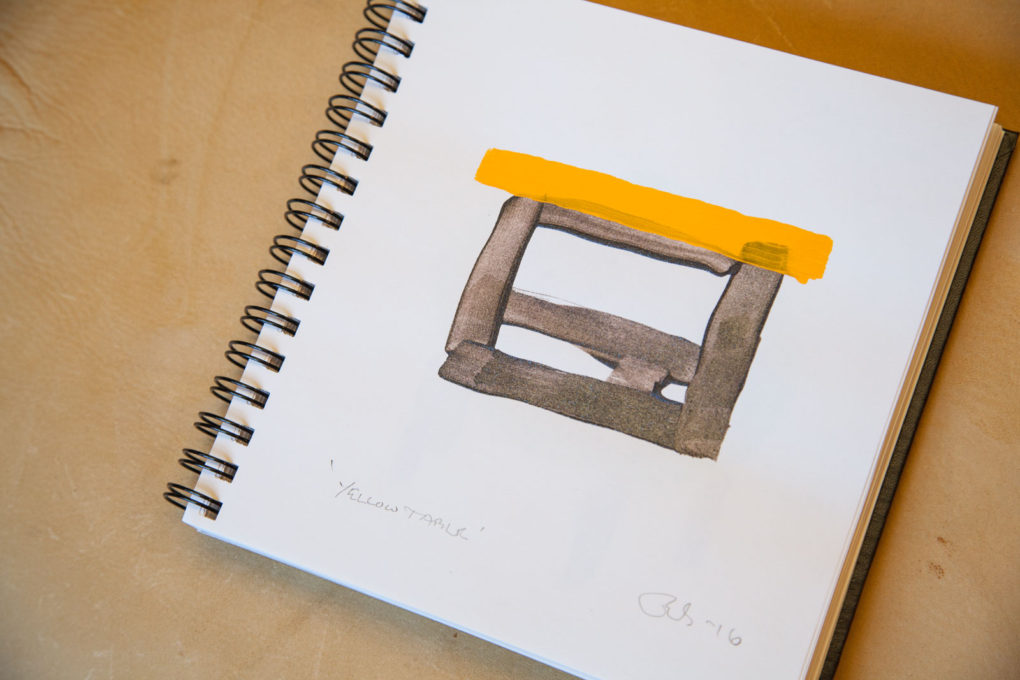

Enjoy Lora’s pics of John’s art work, plus John and Bartley’s beautiful home. As you might expect from two very artistic and design minded people, their abode is the perfect balance of comfort and aesthetically pleasing interior design.

John, what was your path to becoming an artist? Were you always artistic?

My grandmother studied painting at Pratt during WW1 – her name was Bernice Rockwell, she’s distantly related to Norman. When granddaddy died she spent many weekends up there in Massachusetts with the Rockwells. I got watercolor lessons from my grandmother and when I was 16 I met an architect named Walter H. Kilham, Jr. and Walter taught me how to use all the woodworking machinery in his basement. It turned out he was quite a famous guy; he was the youngest architect to work on the Rockefeller Center during the depression. He encouraged me to pursue furniture design, so I went to RIT in Rochester. On weekends I worked for Wendell Castle for $4/hr making his pieces. When I finished going to RIT and I had the Tiffany Foundation grant with Wendell, I lived in NYC and built art galleries and lofts. Then I was in the Peace Corps in West Africa. When I came back I was flat broke and Robert Motherwell bought a chair of mine, the colored chair. It sat in his library until the day he died.

In 1975, Bob Motherwell hired me to be the first full time assistant he ever had.

Was Robert Motherwell already well known at that point?

He was one of the original abstract expressionists in the 40s and 50s, same crowd as Jackson Pollock and all those guys. Bob Motherwell was considered the spokesman for that entire group, because he was probably the only one that had any college education whatsoever and was highly literate, a good writer too. So he and I hit it off right away, I sold him the chair, and we got to be friends. I’d stop by and have dinner there.

I worked for him for 3 years full time and some people have called that time in my life my art world fast lane, or my introduction to the fast lane, because pretty much all the most important people in the art world, sooner or later filtered through the studio either to buy something, or to visit, or do an article. A film crew would turn up from Time Magazine and I’d have to make eggs for 12 people.

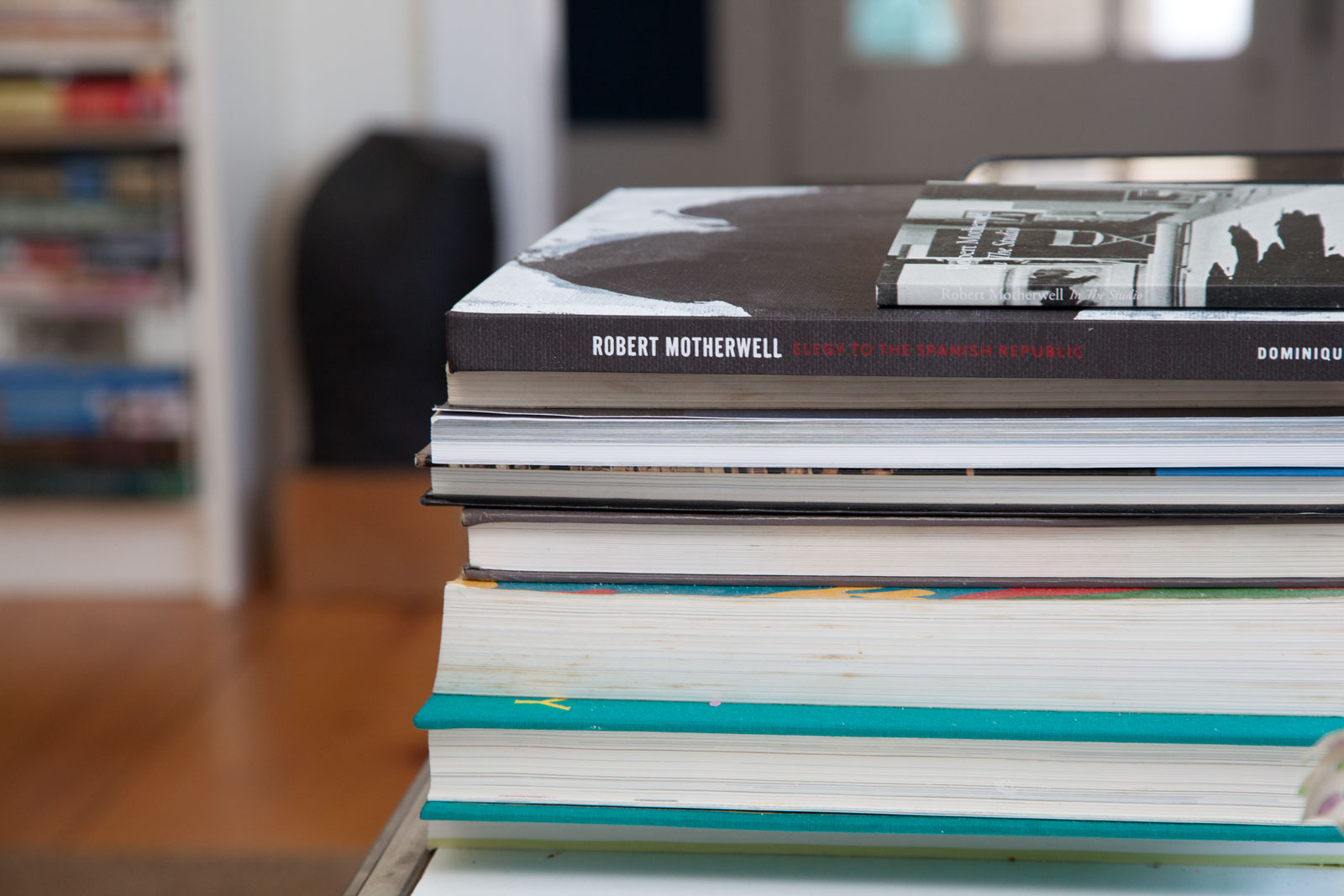

Twenty years after his death, there’s a huge Motherwell revival.

What would you say is the most important thing you learned from Motherwell?

The most important thing is not a visual thing; it’s a sort of a concept, which is that all art, especially good abstract art, has a subject matter. An identifiable subject matter that’s central to the existence of the painting, or sculpture, or whatever it is.

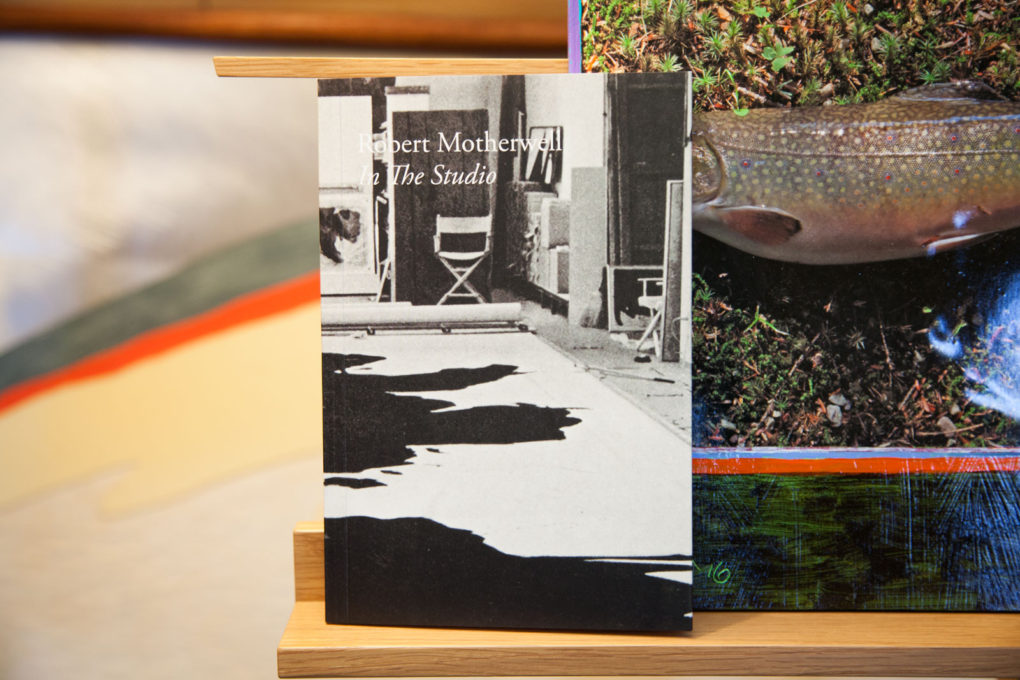

Tell us about your book Robert Motherwell, In the Studio, by John E. Scofield.

My book is a very autobiographical thing, about the 3 years that I worked for Robert Motherwell. It’s loaded with photos. There was a little room off one of the main studio, which was called John’s studio. I had painting supplies and would build racks for him. He’d do these big collages, 6’ high and I’d constantly be moving them around, to create the right mood for him.

The book is published by the Bernard Jacobsen gallery in London.

And after 3 years you went out on your own?

When you work with an artist of this stature, you’re 1/3 artist 1/3 family member, and 1/3 servant. It’s practically a 24/hr day job and it burns a lot of people out. At the end of three years I was lucky enough to have my first sculpture commission by an early computer company in CT, called Data Dimensions. They were building a new building and asked me to do a fairly large piece of sculpture for the main entrance.

Are you producing art every day?

Pretty much; something, yes. You have to tie it into the rhythm of the family…

But don’t you feel like you have to be in the mood?

No. No, you just have to the discipline to do it. Maybe you’ll do three terrible things in a row and the fourth one you really get it right. It’s totally random. You just have to apply yourself, like a plumber going to work and getting their wrenches out.

I’m reading Vivienne Westwood’s autobiography just now…and they talk about punk and the artistic movements in the 70s. Do you think there’s any big thing in art happening right now? Will we look back in 30 years or so and say, oh, that was the “thing”?

Well it’s possible, but we’re in a thing called a post-modern period now. That’s the next thing that we have to break out of. It’s going to be the young people that do that. It’s not going to be my generation. I’m still a modernist. I’ve skipped the post-modern movement entirely.

Tell us about the folding music stand?

When I went to RIT they had a thing called woodworking and furniture design. People would be in the studios until midnight. A talented young woman in metals asked if I would make a music stand – because she had to give one to a relative – and she’d trade me for a belt buckle. I got so obsessed with this idea that I didn’t go to classes, I didn’t do anything for a week, except work on the music stand, literally night and day. After 5 or 6 days, I finally realized the only way it was going to work was if you took one of the legs and curved it. Now it makes an equilateral triangle and when you put the music or art book “the load” on the music shelf, that center of gravity goes right down to the center of the triangle on the floor.

How did the stand end up in the Museum of Modern Art?

The design sat in the closet for 10 years…then I entered it in the 1982 Progressive Architect International Furniture Design competition.

There were over 500 entries from 21 countries. They had a bunch of really famous jurors. Mine was the only unanimous decision of the jurors. So it got published and exhibited all over the world, for the next year or so, and somebody said I should submit it to the Modern to see if it could get into the collection.

It was a serious of accidents in a way. The letter I wrote sat for over a year there until Stuart Wrede became director of the Architecture and Design department at the Modern, and finally took it to his committee where it was unanimously voted it in.

2 bloggers and an ancient Egyptian wood lathe

Post interview, John asked us if we’d like to experience using a replica of an ancient Egyptian wood lathe. Since 1995, John has been giving materials seminars and workshops for a class in Ancient Furniture at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts in New York. The workshops study furniture design and production techniques going back to an ancient world, roughly 50 centuries before the present. The course was originated and is taught by Dr. Elizabeth Simpson.

Of course, we said yes….

If one was to become proficient at wood turning (we’d maybe need 10 years more practice) we could make this!

Thanks for the cuppa and chat John and Bartley, and for showing us how hard it would have been for us to have been Egyptian slaves!

John E. Scofield

PO Box 761

Sharon, CT 06069

johneverettscofield@gmail.com

Art and Design Blog: johneverettscofield.blogspot.com

Website: www.johnscofield-designs.com

Facebook / Art Projects: www.facebook.com/jescofield

Pics: Lora Words: Bev